Antipsychotics and Stroke Risk in Seniors with Dementia: What Doctors Won’t Always Tell You

Why Antipsychotics Are Still Prescribed to Seniors with Dementia

It’s a heartbreaking scene: an elderly parent with dementia pacing the hallway at 3 a.m., yelling, hitting, or refusing to eat. The caregivers are exhausted. The nursing home staff is overwhelmed. Someone suggests an antipsychotic - a quick fix to calm things down. It happens every day. But what no one tells you is that this common solution could be putting your loved one’s life at risk.

Antipsychotics like risperidone, olanzapine, and haloperidol were never meant for dementia patients. They were designed for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Yet, since the 1990s, they’ve been routinely used to manage behavioral symptoms in seniors with Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia - aggression, hallucinations, paranoia, and agitation. The problem? These drugs don’t fix the root cause. They just suppress symptoms. And in doing so, they dramatically increase the chance of stroke - and death.

The FDA Warning You Might Not Have Heard

In 2005, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration slapped a black box warning on all antipsychotic medications - the strongest possible alert. It said: “Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with atypical antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death.” The warning wasn’t vague. It was backed by data from 17 clinical trials involving over 3,000 elderly patients. Those taking antipsychotics had a 1.6 to 1.7 times higher risk of dying than those on placebo.

The deaths weren’t from overdoses or rare side effects. They were from strokes, heart failure, and infections - all linked to how these drugs affect the brain and body. Even more alarming? The risk doesn’t wait months to show up. Studies show stroke risk spikes within days or weeks of starting the medication. That means even a short trial - say, two weeks to “see if it helps” - could be deadly.

Typical vs. Atypical: Does One Type Safer?

Doctors often say, “We switched you from haloperidol to quetiapine because it’s safer.” But that’s misleading. The old drugs - called typical antipsychotics (like haloperidol and fluphenazine) - are known to cause movement disorders and sedation. The newer ones - atypical antipsychotics (like risperidone, aripiprazole, olanzapine) - were marketed as gentler. But when it comes to stroke risk, the difference is minimal.

Research from the American Journal of Epidemiology (2015) followed over 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries. It found that while atypical antipsychotics cause more weight gain, diabetes, and metabolic issues, they don’t protect against stroke. In fact, both types increase stroke risk by about 80%. A 2023 review in Neurology analyzed five major studies and found that long-term use of typical antipsychotics carried a slightly higher stroke risk than atypicals - but only after 90 days. For short-term use? The risks were nearly identical.

Bottom line: Neither class is safe. The idea that one is “better” is a myth. Both carry the same deadly trade-off: calming behavior at the cost of brain health.

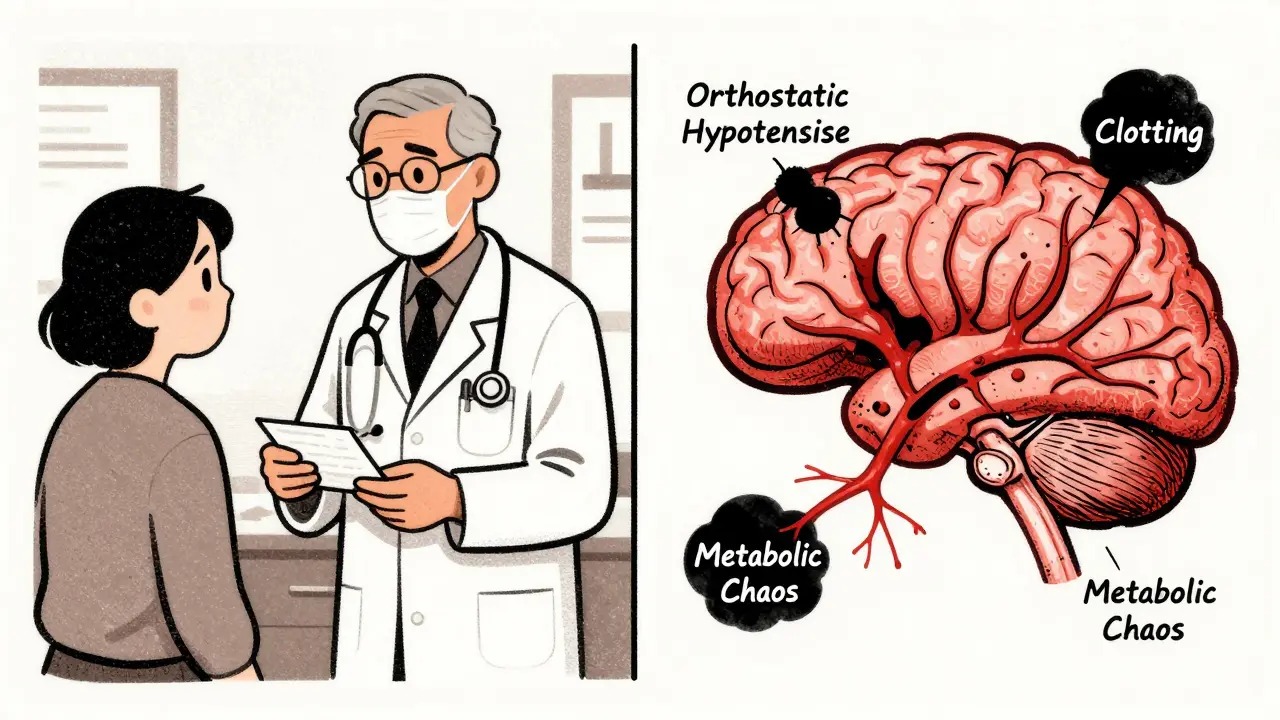

How Antipsychotics Trigger Stroke

It’s not just one thing. Antipsychotics attack the body in multiple ways to raise stroke risk:

- Orthostatic hypotension: These drugs lower blood pressure when standing up, causing dizziness and falls - which can trigger clots or bleeding in the brain.

- Metabolic chaos: They cause rapid weight gain, high blood sugar, and abnormal cholesterol - all known stroke risk factors.

- Neurotransmitter disruption: By blocking dopamine and serotonin, they interfere with blood vessel control in the brain, reducing blood flow when it’s needed most.

- Increased clotting: Some studies suggest antipsychotics make blood stickier, raising the chance of blockages.

One study of Veterans Affairs patients showed that stroke risk jumped immediately after starting the drug - even in people who had no prior history of high blood pressure or heart disease. This isn’t about aging. It’s about the drug’s direct effect on the vascular system.

Why Do Doctors Still Prescribe Them?

If the risks are this clear, why are these drugs still in use? The answer is simple: there aren’t enough alternatives.

In nursing homes, staff are stretched thin. A resident who won’t sit still, hits caregivers, or screams all night is a logistical nightmare. Antipsychotics are fast, cheap, and easy. Non-drug approaches - like adjusting lighting, playing familiar music, changing routines, training staff in dementia communication - take time, training, and resources. Most facilities don’t have them.

And here’s the cruel irony: often, the behavioral symptoms that trigger the prescription - pacing, yelling, resisting care - are signs of pain, confusion, or fear. The person isn’t being difficult. They’re trying to communicate. But antipsychotics silence the message, not the cause.

What the Guidelines Actually Say

The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria - the gold standard for safe prescribing in seniors - has said since 2015: “Antipsychotics should be avoided for treating behavioral symptoms of dementia.” The American Heart Association agrees: “Antipsychotic therapy should only be considered after non-drug strategies have been fully tried.”

But guidelines are not laws. And many doctors, especially in busy clinics or nursing homes, don’t follow them. A 2022 study found that nearly 30% of nursing home residents with dementia were still on antipsychotics - even though 70% of them had no diagnosis of psychosis. Many were on the drugs for “agitation” or “restlessness” - symptoms that don’t qualify for FDA-approved use.

Worse, many prescriptions are never reviewed. A patient might get started on risperidone after a bad week, then stay on it for months or years - with no reevaluation. The drug becomes routine, not treatment.

What to Do Instead

If your loved one is on an antipsychotic, here’s what you can do:

- Ask for a medication review: Request a full list of all prescriptions and ask, “Is this still necessary?”

- Request a non-drug plan: Ask the care team to document a behavioral strategy - like scheduled walks, calming music, or one-on-one time with a volunteer.

- Check for hidden causes: Pain, urinary tract infections, constipation, or poor vision can trigger agitation. Get a full medical workup.

- Push for a taper: If the drug has been used for more than a few weeks, ask for a slow, monitored reduction. Stopping cold turkey can cause withdrawal seizures or rebound aggression.

- Find dementia-specialized care: Some memory care units train staff in non-pharmacological approaches. Ask if the facility is certified by the Alzheimer’s Association or similar programs.

The Real Cost of a Quick Fix

There’s no sugarcoating this: antipsychotics in dementia patients kill. They don’t just increase stroke risk - they shorten lives. A 2020 study of older veterans found that those on antipsychotics died sooner - even if they didn’t have a stroke. The drugs seem to accelerate decline.

And the worst part? The people who benefit most from these drugs are often unable to tell you they feel worse. They can’t say, “I feel dizzy,” or “My chest is tight,” or “I don’t want this pill.” Their voices are silenced - not just by dementia, but by the very medication meant to help.

There are no magic solutions for dementia’s behavioral symptoms. But there are better ones than drugs that steal time from the people we love. The question isn’t whether antipsychotics work to calm behavior. They do. The question is: at what cost? And is that cost worth it?

When Might an Antipsychotic Be Justified?

There are rare cases where the risk might be worth it - but they’re few. The American Heart Association says antipsychotics may be considered only if:

- The person is a danger to themselves or others (e.g., violent outbursts, trying to jump out of windows).

- All non-drug options have been tried for at least two weeks.

- The family and care team agree it’s a last resort.

- The dose is the lowest possible, and the plan includes weekly reviews to see if it can be stopped.

Even then, the goal isn’t lifelong use. It’s to get through a crisis - then get off the drug as soon as possible.

What Families Need to Know

You’re not alone if you’ve been pressured to agree to antipsychotics. Many families feel guilty saying no - afraid they’re being “harsh” or “not doing enough.” But saying no to a dangerous drug isn’t refusal. It’s protection.

Ask your doctor:

- “What specific symptom is this drug targeting?”

- “What are the chances this will cause a stroke?”

- “What happens if we stop it?”

- “Can we try a non-drug approach for 30 days first?”

And if the answer is, “It’s the only thing that works,” ask: “Then why are we still using it when we know it kills?”

Do antipsychotics help with dementia symptoms like agitation or aggression?

Yes, they can reduce agitation or aggression in the short term. But they don’t treat the cause. They just suppress behavior. And the trade-off - a nearly 80% higher risk of stroke - makes them dangerous for most seniors. Non-drug approaches like music therapy, structured routines, and one-on-one engagement are safer and often just as effective.

Are atypical antipsychotics safer than typical ones for dementia patients?

No. While atypical antipsychotics (like risperidone or olanzapine) were once thought to be safer, research shows both types increase stroke risk by about the same amount - around 80%. Atypicals may cause more weight gain and diabetes, but they don’t protect against stroke or death. Neither class is safe for long-term use in dementia.

How quickly can antipsychotics cause a stroke in seniors with dementia?

Stroke risk rises within days or weeks of starting the medication. A 2012 study of Veterans Affairs patients found that even brief exposure - less than 30 days - was enough to significantly increase stroke risk. This contradicts the old belief that only long-term use was dangerous. The danger starts immediately.

What are the alternatives to antipsychotics for managing dementia behaviors?

Non-drug strategies include music therapy, regular physical activity, adjusting lighting and noise levels, identifying and treating pain or infections, using calming routines, and training staff in dementia communication. Studies show these approaches reduce agitation as effectively as drugs - without the risk of stroke or death.

Can antipsychotics be safely stopped if a senior has been on them for months?

Yes - but they must be tapered slowly under medical supervision. Stopping abruptly can cause withdrawal symptoms like nausea, anxiety, or even seizures. Work with a doctor to reduce the dose gradually over weeks or months while monitoring for return of behaviors. Often, those behaviors improve as the body adjusts - and the person becomes more comfortable without the drug’s sedating effects.

12 Comments

Darren Gormley

January 29 2026LMAO another anti-pharma rant. 🤡 Everyone knows these drugs save lives in nursing homes. Without them, you’d have residents throwing feces and breaking windows. Stop scaremongering with ‘stroke risk’ - it’s 1.7x, not 170x. Get real.

Claire Wiltshire

January 30 2026I appreciate the thorough breakdown, but I’m disturbed by how normalized this is. My mother was on risperidone for 18 months after a minor episode of yelling. No one ever mentioned stroke risk - not the doctor, not the nurse, not the social worker. It was just ‘standard protocol.’ By the time we questioned it, she’d lost 15 pounds and couldn’t walk without assistance. These drugs don’t calm dementia - they sedate it. And we call that care?

Donna Fleetwood

January 31 2026This is so important. I used to work in memory care and saw firsthand how music therapy and scheduled walks reduced aggression way better than meds. One lady would scream for hours until we played Frank Sinatra - then she’d smile and sway. No side effects. No hospital trips. Just human connection. We need more of that, not more pills.

Mike Rose

February 2 2026idk why people make this so complicated. old people get weird. give em a pill. problem solved. why waste time with music and walks when you can just chill em out? its not like they remember anyway.

Niamh Trihy

February 2 2026I’ve seen this play out in Ireland too. Families feel guilty saying no, but they’re not being cruel - they’re being protective. The real tragedy is how few facilities have the staffing or training to offer alternatives. This isn’t a medical failure - it’s a systemic one. We need funding for non-pharmacological care, not just more prescriptions.

Beth Cooper

February 2 2026You know who really profits from this? Big Pharma + nursing home corporations. They’ve been pushing these drugs since the 90s because it’s cheaper than hiring enough staff to actually care. The FDA warning? A PR stunt. The real data? Suppressed. Google ‘Dementia Drug Conspiracy 2017’ - you’ll find whistleblower emails. They knew. They still do.

Kathleen Riley

February 4 2026The ethical implications of pharmacologically suppressing the behavioral manifestations of neurodegenerative disease, while simultaneously eroding the patient’s autonomic and cerebrovascular integrity, constitute a profound moral quandary. One is compelled to ask: when the preservation of institutional convenience supersedes the sanctity of biological autonomy, have we not transgressed the foundational tenets of medical ethics?

Beth Beltway

February 6 2026You’re all just emotionally manipulated by anecdotal stories. The data says 80% increased stroke risk - that’s not ‘dangerous,’ that’s statistically significant. But guess what? The alternative is chaos. You want to let an 89-year-old punch a nurse because you’re too sentimental to give her a pill? That’s not compassion. That’s negligence. Wake up.

Bobbi Van Riet

February 7 2026I’ve been caring for my dad with late-stage Alzheimer’s for five years. We tried antipsychotics once - he got so dizzy he fell and broke his hip. After that, we worked with a dementia specialist who taught us to read his body language. Turns out, he wasn’t ‘agitated’ - he was in pain from a UTI. Once we treated that, the ‘behavior’ disappeared. I wish someone had told us that before. Don’t assume the behavior is the problem. Look for the cause.

Yanaton Whittaker

February 7 2026America is soft. Back in my day, we didn’t coddle old people with music and hugs. We gave them a shot and kept them quiet. If they die a little sooner? So what? They were gonna die anyway. Stop making everything a crisis. Just fix the problem.

Katie and Nathan Milburn

February 9 2026I’ve reviewed this article with my geriatrician. The data is consistent across multiple cohorts. The key takeaway: antipsychotics are not contraindicated - they are to be used with extreme caution, only after exhaustive non-pharmacological interventions, and with documented, time-bound reevaluation protocols. The issue isn’t the drug. It’s the lack of oversight.

Melissa Cogswell

February 10 2026My aunt was on haloperidol for 3 years. We tapered her off slowly over 8 weeks. The first week was rough - she was restless, confused. But by week 4, she started recognizing my kids again. She hadn’t done that in over a year. It wasn’t magic. It was just her brain waking up. I wish we’d tried this sooner.