How Government Controls Generic Drug Prices in the U.S. Today

When you fill a prescription for a generic pill - say, lisinopril for blood pressure or atorvastatin for cholesterol - you expect it to be cheap. And in most cases, it is. But the price you pay at the pharmacy counter isn’t random. It’s the result of a complex web of federal rules, rebate systems, and market forces that most people never see. The U.S. government doesn’t set generic drug prices directly like many other countries do. Instead, it uses indirect levers to drive costs down. Understanding how this system works can help you make smarter choices, avoid surprise bills, and know when something’s wrong.

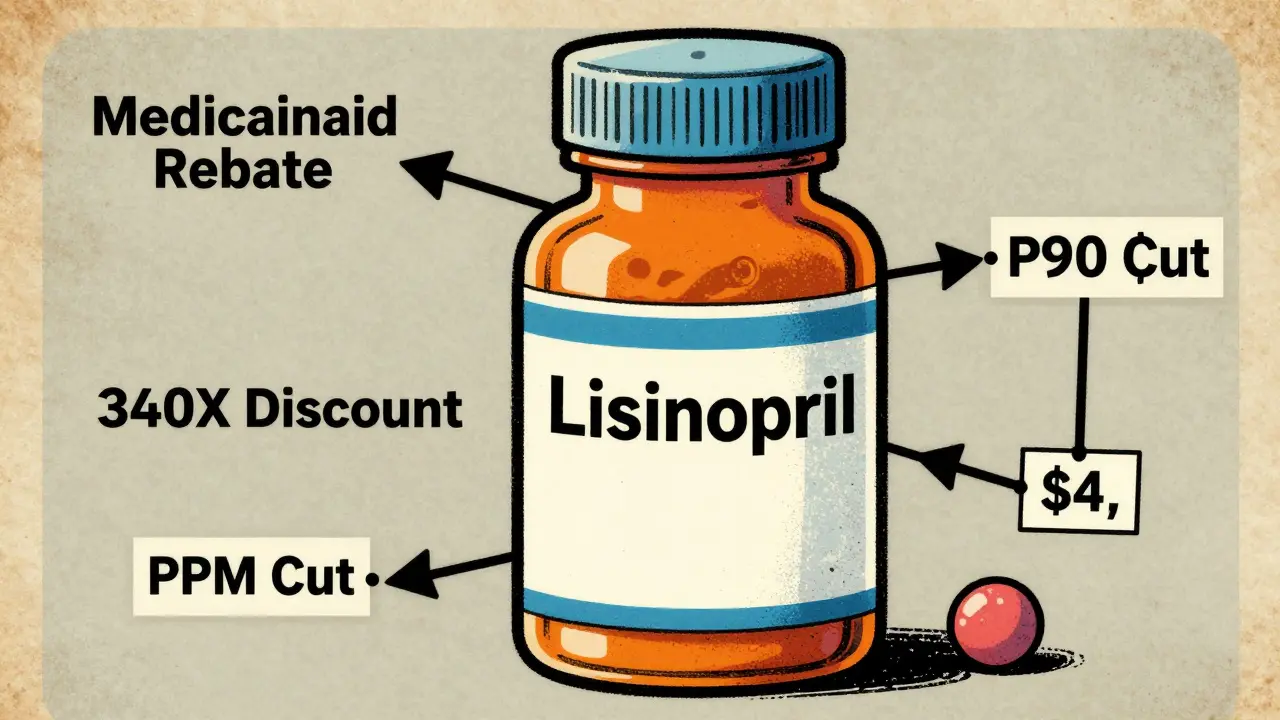

How Medicaid Keeps Generic Prices Low

The biggest force holding down generic drug prices in the U.S. is the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. Since 1990, drugmakers have been required to pay rebates to state Medicaid programs for every generic pill sold. The math is simple but powerful: manufacturers must pay back either 23.1% of the average price they charge wholesalers, or the difference between that price and the lowest price they give to any private buyer - whichever is higher. In 2024, these rebates totaled $14.3 billion, and 78% of that came from generic drugs. That’s not charity. It’s a legal obligation tied to Medicaid participation. Without this program, many generic drugs would cost significantly more. The rebate system doesn’t cap prices, but it forces manufacturers to compete on price to stay profitable. If one company slashes its price to win a contract, others have to follow or lose sales.Medicare Part D and the Out-of-Pocket Cap

For seniors on Medicare, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 changed the game. Before 2025, beneficiaries paid 25% coinsurance for generics during the initial coverage phase, and once they hit $8,000 in out-of-pocket costs, they entered catastrophic coverage with minimal payments. Now, thanks to the IRA, the cap is $2,000 per year. That means if you take five or six generic medications, your annual spending is locked in. Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) beneficiaries - those with incomes under 150% of the federal poverty level - pay nothing or just $0 to $4.90 per generic prescription. That’s not a discount; it’s a safety net. But here’s the catch: the actual price your plan pays the pharmacy isn’t always what you see. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) negotiate rebates behind the scenes, and most of that savings never reaches you. A 2025 Senate report found that 68% of generic drug rebates are kept by PBMs, not passed on to patients.Why Generic Prices Vary So Much

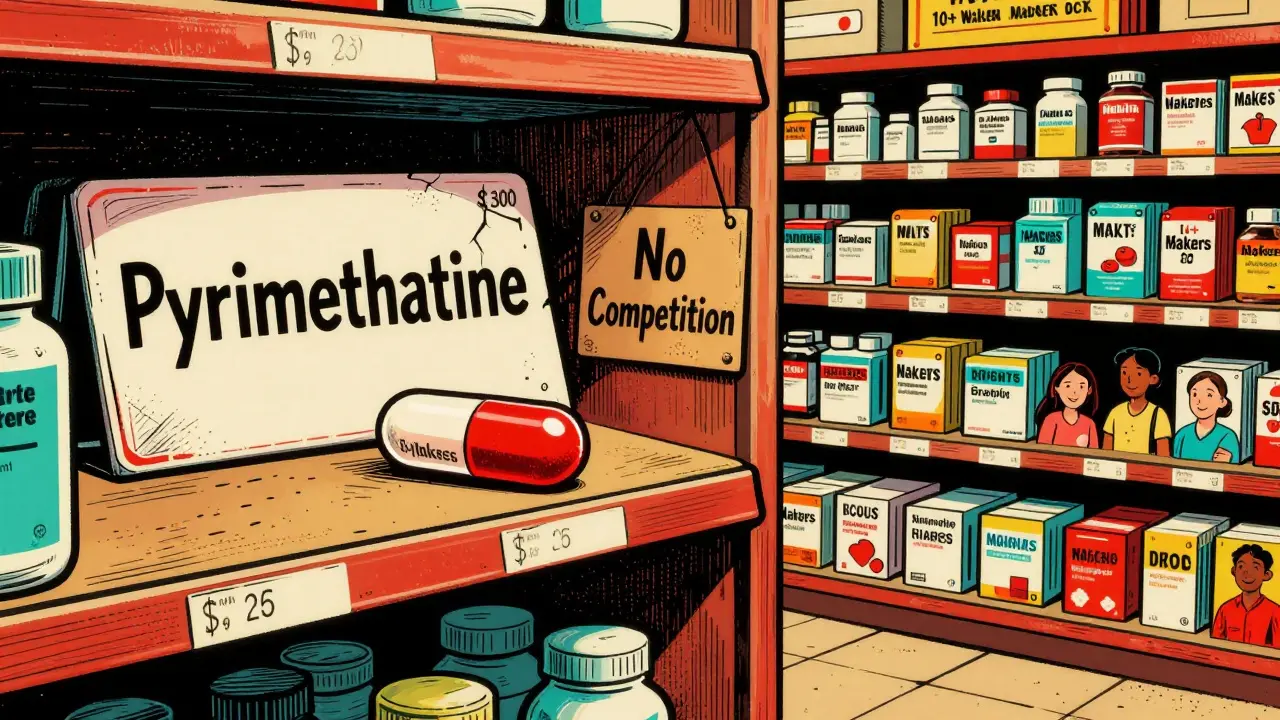

You might think all generic metformin is the same. It is - chemically. But the price? Not even close. One pharmacy might charge $4 for a 30-day supply. Another might charge $45. Why? It depends on your insurance plan’s formulary, the manufacturer, and whether your pharmacist is allowed to substitute. In 49 states, pharmacists can switch your generic brand without asking - as long as it’s approved as bioequivalent. But different manufacturers have different pricing deals with insurers. So if your plan has a deal with Teva but your pharmacist accidentally dispenses a Mylan version, your copay could jump from $0 to $20. That’s not a mistake - it’s how the system is built. The real problem shows up in low-competition markets. Take pyrimethamine (Daraprim), a drug used to treat rare infections. In 2024, when only two companies made it, the price spiked 300%. No one could negotiate it down because there was no competition. The same thing happened with some antibiotics and thyroid meds. The system works well when there are 10 or more manufacturers. When there are two or three, prices can go haywire.

The 340B Program: Hidden Savings for the Poor

One of the most effective but least-known programs is the 340B Drug Pricing Program. It requires drugmakers to sell outpatient medications - including generics - at steep discounts to hospitals and clinics that serve low-income patients. These aren’t charities. They’re safety-net providers: community health centers, rural hospitals, free clinics. The discounts range from 20% to 50% below the average manufacturer price. A 2025 survey found that 87% of these clinics reported better patient adherence because people could actually afford their meds. But here’s the twist: the savings don’t always go to the patient. Some clinics use the money to cover operating costs. Still, for someone who can’t afford $100 a month for insulin or blood pressure meds, 340B makes the difference between taking the drug and skipping doses.What’s Changing in 2026 and Beyond

The biggest shift coming is Medicare’s new power to negotiate prices for certain high-cost drugs. But here’s the key: generic drugs are mostly exempt. Why? Because the government assumes competition keeps them cheap. But that assumption is breaking down. In 2027, CMS will start negotiating prices for generic versions of apixaban (Eliquis) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto). These are blood thinners used by over 5 million Medicare beneficiaries. Even though they’re generics, only a few companies make them. The CBO estimates this could cut prices by 25-35%. If it works, it could become a model for other low-competition generics. Meanwhile, the government is pushing for more transparency. Starting in April 2025, manufacturers must disclose their actual production and distribution costs before a drug hits the market. It’s not a price cap - but it’s a start. If you know how much it costs to make a pill, you can question why it’s sold for 10 times that.

What Experts Say - And Why They Disagree

Some experts, like Dr. Peter Bach from Memorial Sloan Kettering, argue the U.S. pays 138% more for generics than other rich countries because we lack centralized buying power. He points to the VA, which gets 40-60% discounts by negotiating bulk purchases. Why can’t Medicare do the same? Others, like Dr. Mark McClellan and the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy, warn that direct price controls could hurt innovation. Generic manufacturers already operate on thin margins - often under 15% profit. If prices drop too far, some may quit the market, leading to shortages. David Epstein, former CEO of Novartis, says excessive controls could kill progress in drug delivery systems and manufacturing efficiency. The Congressional Budget Office says expanding Medicare negotiation to more generics could save $12.7 billion over ten years. That sounds like a lot - until you realize it’s just 0.3% of total U.S. drug spending. But for the 30% of Americans who struggle to afford meds, that $12.7 billion means thousands of people can actually take their pills.What You Can Do Right Now

You can’t change the system overnight. But you can work within it.- Use the Medicare Plan Finder tool every year. Don’t assume your plan stays the same. Formularies change, and so do copays.

- Ask your pharmacist: "Is there a different generic version of this drug that’s cheaper under my plan?" Sometimes switching brands cuts your cost in half.

- If you’re on Medicare and pay more than $2,000 a year for meds, check if you qualify for LIS. It’s not automatic - you have to apply.

- For non-Medicare users, ask if your pharmacy offers a cash discount. Many chains sell common generics for $4-$10 without insurance.

- Check if your clinic participates in 340B. If you’re low-income, you might qualify for deeply discounted meds there.

Why This Matters

Generic drugs are the backbone of affordable healthcare in America. They make up 90% of all prescriptions but only 23% of total spending. That’s the power of competition - when it works. But when competition fails, people suffer. A 68-year-old in Florida might pay $15 for lisinopril one month, then $90 the next because her insurer switched manufacturers. That’s not a glitch. It’s the system. The government doesn’t control generic prices the way Canada or Germany does. But it doesn’t need to. It already has powerful tools: rebates, caps, transparency rules, and now, limited negotiation. The real challenge isn’t policy - it’s enforcement. Making sure rebates reach patients. Making sure competition stays real. Making sure no one has to choose between food and their blood pressure pill.Does the U.S. government set prices for generic drugs directly?

No, the U.S. federal government does not directly set prices for generic drugs in the commercial market. Instead, it uses indirect mechanisms like Medicaid rebates, Medicare Part D cost caps, and the 340B program to lower prices. Manufacturers are required to provide rebates to Medicaid, but they set their own list prices. The government influences pricing through rules and incentives, not price ceilings.

Why do generic drug prices vary so much between pharmacies?

Generic drug prices vary because different manufacturers sell the same drug at different prices, and insurance plans negotiate separate deals with each one. Your pharmacy’s contract with your insurer determines which generic brand is covered and at what cost. If your plan has a deal with Teva but your pharmacist dispenses a Mylan version, your copay could jump. Also, cash prices at pharmacies are often unrelated to insurance pricing.

Are generic drugs cheaper in other countries?

Yes. According to a 2025 KFF analysis, U.S. generic drug prices are 1.3 times higher than the average of 32 other OECD countries. Countries like Canada, the UK, and Germany use direct price controls or reference pricing, where prices are set based on what other nations pay. The U.S. relies on market competition, which works well for common drugs but fails when only a few manufacturers remain.

Can Medicare negotiate prices for generic drugs?

Generally, no - but that’s changing. The Inflation Reduction Act exempts most generics from Medicare price negotiation because of assumed competition. However, starting in 2027, Medicare will negotiate prices for generic versions of high-cost drugs like apixaban and rivaroxaban, where only a few manufacturers compete. This marks the first time Medicare will directly negotiate generic drug prices, and it could set a precedent for others.

What’s the 340B program, and how does it help with generic drug costs?

The 340B Drug Pricing Program requires drugmakers to sell outpatient medications - including generics - at deep discounts to safety-net hospitals and clinics that serve low-income patients. Discounts range from 20% to 50% below the average manufacturer price. These savings help clinics keep medications affordable for patients who can’t pay full price. While not all savings go directly to patients, the program has improved adherence for 87% of participating clinics.

Why do some generic drugs suddenly become much more expensive?

When only one or two manufacturers make a generic drug, competition disappears. That’s when prices can spike - sometimes by 300% or more. This happened with pyrimethamine (Daraprim) and some antibiotics. The FDA approves generics, but it doesn’t ensure enough manufacturers enter the market. Without competition, there’s no pressure to keep prices low, and manufacturers can raise prices without fear of losing customers.

How can I find the cheapest generic version of my medication?

Use the Medicare Plan Finder tool if you’re on Medicare. For others, ask your pharmacist: "Is there a different generic brand of this drug that’s cheaper under my insurance?" Also, check cash prices at pharmacies like Walmart, Costco, or CVS - many common generics cost $4-$10 without insurance. Don’t assume your current brand is the cheapest - switching manufacturers can save you hundreds a year.