Hyponatremia and Hypernatremia in Kidney Disease: What You Need to Know

When your kidneys start to fail, they don’t just stop filtering waste. They also lose their ability to keep your sodium levels in check. That’s when problems like hyponatremia and hypernatremia creep in - and they’re far more common than most people realize. In fact, about 1 in 5 people with advanced kidney disease will develop one of these sodium disorders. And while they might sound technical, the consequences are very real: confusion, falls, broken bones, and even higher risk of death.

What Exactly Are Hyponatremia and Hypernatremia?

Hyponatremia means your blood sodium is too low - under 135 mmol/L. Hypernatremia is the opposite: sodium above 145 mmol/L. Sodium isn’t just table salt. It’s the main electrolyte that controls how much water is in and around your cells. When sodium drops, water rushes into cells, making them swell. When sodium rises, water leaves cells, making them shrivel. Your brain is especially sensitive to these shifts.

In healthy people, kidneys adjust urine output to keep sodium steady. But when kidney function drops below 30 mL/min/1.73m² (Stage 4 or 5 CKD), that system breaks down. You can’t make enough dilute urine to flush out excess water - so hyponatremia happens. Or you can’t concentrate urine to hold onto water - so hypernatremia kicks in.

Why Kidney Disease Makes Sodium Problems Worse

Your kidneys handle sodium in three ways: filtering it, reabsorbing it, and excreting it. In early kidney disease (Stages 1-2), your kidneys still work well enough to get rid of salt and water - but they have to work harder. You’ll need to produce more urine to clear the same amount of sodium.

By Stage 3 (GFR 30-59), things get tricky. Your kidneys start losing their ability to concentrate urine. That means if you drink too much water, your body can’t get rid of it fast enough. Sodium gets diluted. This is why many people with CKD develop hyponatremia even without drinking excessive fluids.

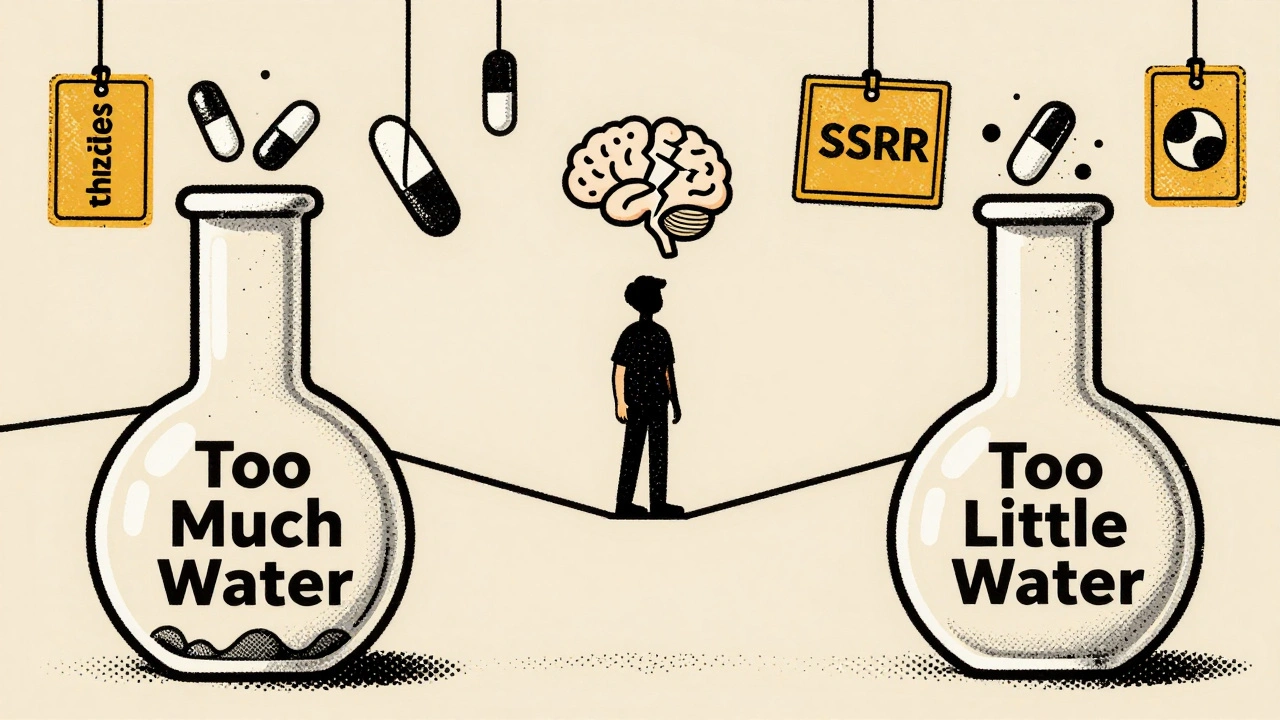

By Stage 4 or 5, your kidneys can barely make urine at all. You’re stuck in a narrow window: drink too little, and you get hypernatremia. Drink too much, and you get hyponatremia. It’s like walking a tightrope with no safety net.

Other factors make it worse:

- Diuretics - especially thiazides - are common in CKD patients with high blood pressure, but they reduce sodium reabsorption and can cause dangerous drops in blood sodium.

- Low-salt diets, meant to protect the heart and kidneys, can backfire. Cutting sodium too hard reduces solute load, which slows water excretion and makes hyponatremia more likely.

- Medications like SSRIs, NSAIDs, and certain antibiotics can trigger inappropriate ADH release, forcing your body to hold onto water even when it shouldn’t.

Types of Hyponatremia in Kidney Disease

Not all hyponatremia is the same. In CKD, it breaks down into three types:

- Euvolemic hyponatremia - Most common (60-65% of cases). Your total body water is high, but your blood volume looks normal. This happens because your kidneys can’t excrete free water. Thiazide diuretics are a major culprit here.

- Hypervolemic hyponatremia - Seen in 15-20% of cases. You’re swollen with fluid (edema), but sodium is still low. This happens in advanced CKD with heart failure or nephrotic syndrome. The body holds onto water because it thinks it’s dehydrated.

- Hypovolemic hyponatremia - Least common (15-20%). You’ve lost both salt and water, but lost more salt. This can come from vomiting, diarrhea, or salt-wasting kidney diseases like Bartter syndrome.

Hypernatremia is less common but more dangerous. It usually happens when someone can’t drink enough water - think elderly patients with dementia, or those on dialysis who miss fluid access. It can also occur if you’re given too much sodium through IV fluids or tube feeding.

Why This Isn’t Just a Lab Number

Many doctors treat hyponatremia like a lab result to fix. But it’s not. It’s a warning sign.

Studies show people with mild hyponatremia (130-134 mmol/L) have a 1.79 times higher risk of dying than those with normal sodium. For those with severe hyponatremia (<125 mmol/L), the risk jumps to over 2 times higher.

The damage isn’t just about death. Hyponatremia causes:

- Cognitive decline - memory loss, trouble concentrating

- Gait instability - 28% of hyponatremic patients stumble or fall, compared to 12% of those with normal sodium

- Falls and fractures - odds increase by 82%

- Osteoporosis - 35% of hyponatremic CKD patients have low bone density vs 23% of others

And here’s the kicker: if you develop hyponatremia while hospitalized, your chance of dying goes up by 28% compared to those who arrive with it already.

Hypernatremia is even more lethal. In ICU settings, it’s linked to a 30-50% mortality rate - especially in older adults with kidney disease.

How to Treat It - Without Making It Worse

Treating sodium disorders in CKD is like defusing a bomb. Go too fast, and you cause brain damage. Go too slow, and you let the damage continue.

For hyponatremia:

- Fluid restriction is first-line - but not the same for everyone. Early CKD: 1,000-1,500 mL/day. Advanced CKD: 800-1,000 mL/day.

- Stop thiazide diuretics if GFR is below 30. Switch to loop diuretics like furosemide.

- Don’t use vaptans (like tolvaptan). They’re approved for hyponatremia, but they don’t work well in CKD and can cause liver damage.

- Correct sodium slowly - no more than 4-6 mmol/L in 24 hours. Faster than that risks osmotic demyelination syndrome - a rare but devastating brain injury.

For hypernatremia:

- Replace water slowly - no more than 10 mmol/L in 24 hours.

- Use oral water if possible. IV fluids should be 5% dextrose, not saline.

- Check for dehydration, fever, or reduced thirst - especially in older adults.

- Review medications. Anticholinergics, opioids, and sedatives can reduce thirst and worsen hypernatremia.

For salt-wasting syndromes (affecting 5-8% of advanced CKD patients), you might need sodium chloride supplements - 4-8 grams per day. But only under close supervision.

The Diet Dilemma

Most CKD patients are told to eat low-sodium, low-potassium, low-protein diets. That’s good for blood pressure and acid balance - but it can backfire for sodium.

When you cut protein and salt, you reduce the solute load your kidneys need to excrete. That makes it harder for them to produce dilute urine. Result? Water builds up. Sodium drops.

A 2023 Japanese study found that patients on strict solute-restricted diets had 3 times higher rates of hyponatremia than those with moderate intake. It’s not that salt is good - it’s that too little salt can be just as dangerous as too much.

Patients need personalized advice. One-size-fits-all diets don’t work. A renal dietitian should review your intake every 3-6 months.

What’s New in 2025

There’s hope on the horizon. In 2023, the FDA approved a new wearable patch that measures sodium levels in your skin fluid - not blood. It gives continuous readings, so you know if your sodium is drifting before you feel symptoms.

Also, the 2024 KDIGO guidelines are expected to recommend individualized fluid targets based on your residual kidney function - not a blanket 1 liter/day rule. If you still make 300 mL of urine a day, you might be able to drink more than someone making zero.

Researchers are also studying the gut-kidney axis. Early data suggests your intestines might help compensate for failing kidneys by absorbing or excreting sodium. If this pans out, we might one day treat sodium disorders with probiotics or gut-targeted drugs.

What You Should Do Now

If you have kidney disease, here’s what to do:

- Ask your doctor to check your sodium level at least twice a year - even if you feel fine.

- Don’t assume low-salt = always better. Talk to a renal dietitian before cutting sodium drastically.

- Know the signs: confusion, nausea, headaches, muscle cramps, or feeling unusually tired could mean low sodium. Dry mouth, extreme thirst, or irritability could mean high sodium.

- Keep a daily fluid log. Write down everything you drink - even coffee, soup, or ice cream.

- Review all your meds. Ask your pharmacist if any could be affecting your sodium.

Hyponatremia and hypernatremia aren’t rare quirks of kidney disease. They’re common, dangerous, and often preventable. The key isn’t just treating the number - it’s understanding how your kidneys are failing, and adjusting your life to match.

Can drinking too much water cause hyponatremia in kidney disease?

Yes - and it’s one of the most common causes. In advanced kidney disease, your kidneys can’t make enough dilute urine to get rid of excess water. Even a few extra glasses of water a day can dilute your blood sodium. That’s why fluid restriction is often part of treatment - not just for swelling, but to prevent dangerous drops in sodium.

Is hyponatremia more dangerous than hypernatremia in CKD?

Both are serious, but hyponatremia is more common and often overlooked. It affects up to 25% of advanced CKD patients and is linked to higher rates of falls, fractures, and death. Hypernatremia is rarer but has higher immediate mortality - especially in elderly or critically ill patients. Neither should be ignored.

Should I stop taking my diuretic if I have low sodium?

Don’t stop on your own. But if you’re on a thiazide diuretic (like hydrochlorothiazide) and have CKD stage 4 or 5, your doctor should consider switching you to a loop diuretic like furosemide. Thiazides become ineffective and increase hyponatremia risk when kidney function drops below 30 mL/min/1.73m².

Can a low-salt diet cause hyponatremia?

Yes - and it’s a hidden risk. Cutting sodium too hard reduces the solute your kidneys need to excrete. That makes it harder for them to flush out water, leading to dilutional hyponatremia. Many patients with advanced CKD develop low sodium because they’ve been told to eat “as little salt as possible” without understanding the trade-off.

How fast should sodium be corrected in CKD patients?

Never faster than 4-6 mmol/L in 24 hours for hyponatremia, and no more than 10 mmol/L in 24 hours for hypernatremia. Faster correction can cause osmotic demyelination - a brain injury that can lead to paralysis, locked-in syndrome, or death. Slower is safer, especially in CKD patients whose kidneys can’t adjust quickly.

12 Comments

nikki yamashita

December 12 2025My grandma had CKD and they kept telling her to drink more water-turns out that nearly landed her in the ER. This post nailed it. Hyponatremia isn’t just ‘drink less’-it’s a tightrope walk.

Audrey Crothers

December 14 2025YES. 😭 I’ve seen this so many times in the clinic. People think ‘low sodium = eat more salt’-nope. It’s way more complex. Kidneys are the real MVPs here, even when they’re failing.

sandeep sanigarapu

December 14 2025This is a well-structured explanation. In India, many elderly patients with renal failure are not monitored for sodium levels due to lack of resources. This should be standard protocol.

Laura Weemering

December 15 2025So... we're just supposed to accept that our kidneys are broken, and now our cells are either swelling or shriveling like raisins? And the drugs meant to help us... are actually making it worse? 😔

It’s not just medical-it’s existential. Who designed this system? Why is survival a mathematical equation we can’t solve?

I used to think ‘hydration’ was simple. Now I know: it’s a betrayal by biology. Water is no longer a gift-it’s a liability.

And the doctors? They just stare at the numbers like they’re reading tea leaves. ‘Your sodium is 132.’ Okay. And? What do I DO?!

They say ‘restrict fluids.’ But what if I’m thirsty? What if my mouth feels like sandpaper? Am I supposed to die of thirst to avoid dying of swelling?

This isn’t medicine. It’s a cruel paradox dressed in white coats.

And then there’s the diuretics-those little pills that promise relief but steal your sodium like a thief in the night.

SSRIs? NSAIDs? They’re not just drugs-they’re silent assassins in the sodium wars.

I’m not even mad. I’m just... tired. Tired of being a walking electrolyte experiment.

And don’t get me started on the ‘low-sodium diet’ crowd. You think you’re helping? You’re just making the water retention worse. It’s like putting a bandage on a hemorrhage.

Who’s writing the guidelines? Someone who’s never had to choose between drinking water and staying alive?

I don’t want to be a statistic. I just want to sip my tea without fearing my brain will swell.

And yet-I’m still here. Still drinking. Still suffering. Still wondering if this is what ‘living with disease’ really means.

Robert Webb

December 15 2025Laura, your comment hits hard-but I want to offer a slightly more grounded perspective. The system isn’t broken because it’s cruel-it’s broken because medicine hasn’t caught up with the complexity of chronic disease. We’re still treating labs like targets instead of signals.

Hyponatremia in CKD isn’t a bug-it’s a feature of a failing system. The body’s trying to survive, not fail.

What we need isn’t just better drugs, but better education-for patients and providers alike. Most patients don’t understand why they can’t just drink when they’re thirsty. They think it’s willpower. It’s physiology.

And yes, diuretics are double-edged swords. But they’re often necessary for hypertension and edema. The problem isn’t the drug-it’s the lack of individualized monitoring.

We need wearable sodium trackers. We need AI that adjusts fluid recommendations in real time. We need to stop treating CKD like it’s a single-disease model.

It’s a systems failure. And we’re all just trying to navigate it with outdated maps.

But we’re learning. Slowly. And that’s something.

Nathan Fatal

December 15 2025Robert’s right-we’re treating symptoms, not systems. But let’s not romanticize the problem. The reality is, in Stage 5 CKD, your kidneys are done. No amount of ‘better education’ brings them back. We need better dialysis protocols. Better fluid management algorithms. And yes-maybe even gene therapies down the line.

Until then, we’re managing a slow-motion collapse. And the worst part? Most patients don’t even know they’re on the tightrope until they fall.

Stop calling it ‘hyponatremia.’ Call it ‘renal water dysregulation syndrome.’ Then maybe people will take it seriously.

Ashley Skipp

December 16 2025Ugh this post is so overdone everyone knows this already why do we need another article about sodium why cant we talk about something new like kidney tumors or something

wendy b

December 17 2025Actually Ashley, you're missing the point. This isn't just about sodium-it's about the pharmaceutical-industrial complex exploiting kidney patients. Did you know that thiazide diuretics were pushed aggressively in the 90s because they were profitable? And now we're stuck with a generation of patients with iatrogenic hyponatremia? It's not medical-it's corporate.

And don't even get me started on how the FDA approves drugs without long-term electrolyte studies in CKD populations. They don't care. They just want the next blockbuster.

They're selling us water restriction like it's a lifestyle choice. It's not. It's a survival tactic forced on us by a system that profits from our suffering.

Someone's making money off this. And it ain't us.

Lawrence Armstrong

December 18 2025WENDY. YOU’RE NOT WRONG. BUT YOU’RE ALSO NOT SEEING THE WHOLE PICTURE. 😈

What if I told you the sodium guidelines were written by nephrologists who’ve never had to live with Stage 5 CKD? What if the ‘low-sodium diet’ was designed by dietitians who’ve never tasted the despair of a dry mouth at 3am?

What if the whole system is a lie?

They say ‘drink less.’ But when you’re on dialysis, your body screams for water. Your cells are begging. And they punish you for listening.

And the worst part? They’ll blame you if you die. ‘You didn’t follow the fluid restriction.’

But who made the restriction? Who decided your kidneys should be your jailer?

It’s not just medicine. It’s control. And they’re using sodium as the leash.

Donna Anderson

December 19 2025OMG YES I JUST HAD THIS HAPPEN TO MY MOM!! She was on a low salt diet and started getting super dizzy and confused-doc said it was ‘dehydration’ but she was drinking like a fish!! Turned out her sodium was 128 😱 We had to go to ER and they fixed it with IV saline in like 2 hours. I’m so glad this post exists!!

Stacy Foster

December 20 2025Lawrence, your emoji are cute but you’re missing the point. This isn’t just about kidneys. It’s about the medical system’s refusal to accept that some patients can’t be ‘fixed.’ We’re being treated like broken machines. And sodium? It’s just the canary in the coal mine.

They don’t want us to live well. They want us to die predictably. So they can move on to the next patient.

And don’t pretend your ‘helpful expert’ status changes that.

Adam Everitt

December 20 2025It’s funny how we obsess over sodium when the real issue is that we’re prolonging life without quality. If your kidneys are at 15% function, should we really be trying to balance electrolytes-or accepting that the body’s done its job?

I’m not saying give up. I’m saying: maybe the goal isn’t to fix sodium. Maybe it’s to fix how we think about death in chronic illness.

But then again… I’m just a guy with a typo-ridden comment and too much time on my hands.