First Generic vs Authorized Generic: How Timing of Market Entry Shapes Drug Prices

When a brand-name drug loses patent protection, the race to sell the first generic version begins. But here’s the twist: the company that made the original drug might launch its own generic version at the exact same time. This isn’t a mistake. It’s a strategy-and it changes everything about how much you pay for medicine.

What’s the difference between a first generic and an authorized generic?

A first generic is the first company to successfully challenge a brand-name drug’s patent and get FDA approval to sell a generic version. This company files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), proving their version works the same as the original. In return, they get 180 days of exclusive rights to sell that generic-no other generic can enter the market during that time. This exclusivity is meant to reward them for the risk and cost of suing the brand-name company in court.

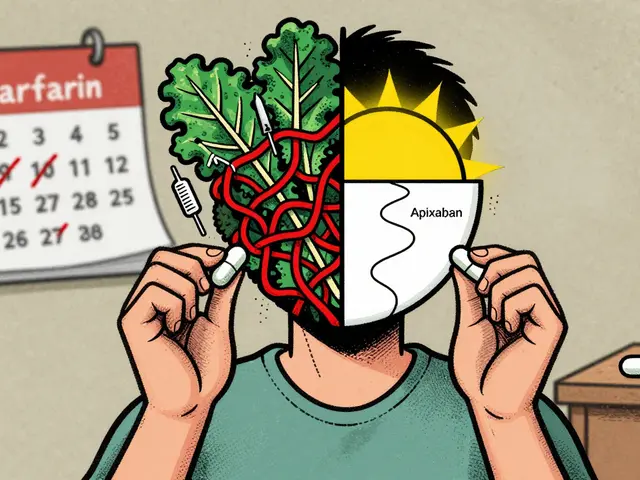

An authorized generic is different. It’s made by the brand-name company-or a partner they’ve approved-and sold under a generic label. It’s identical to the brand drug: same ingredients, same factory, same packaging, just without the brand name. The key? They don’t need an ANDA. They use the brand’s original New Drug Application (NDA), so they can launch anytime-even while the first generic is still enjoying its 180-day exclusivity.

Think of it this way: the first generic is the underdog that fought its way in. The authorized generic is the brand itself, walking in right behind it, wearing a disguise.

Why does timing matter so much?

The whole point of the 180-day exclusivity rule is to give the first generic a chance to make big profits, lower prices fast, and encourage other companies to enter later. But if the brand launches an authorized generic on day one, that plan falls apart.

Here’s what happens: the first generic expected to capture 80% of the market. Instead, they split it 50/50-or worse-with the authorized version. That cuts their revenue in half. And because both versions are priced low, the overall price drop isn’t as deep as it should be.

Research from Health Affairs shows that 73% of authorized generics launch within 90 days of the first generic’s approval. Over 40% launch on the exact same day. That’s not coincidence. It’s calculated.

Take Lyrica (pregabalin). When Teva launched the first generic in July 2019, Pfizer-Lyrica’s maker-immediately rolled out its own authorized generic through Greenstone LLC. Within weeks, Pfizer’s version grabbed about 30% of the market. Teva’s expected $200 million in exclusivity revenue? Cut by nearly half.

How does this affect drug prices?

When a brand-name drug goes generic, prices usually drop 80-90%. That’s the goal. But when an authorized generic enters during the first generic’s exclusivity window, that drop shrinks to 65-75%.

Why? Because now there are two low-priced versions competing, not one. That sounds good, right? But here’s the catch: neither version is priced as low as it would be if there were five or six generics in the market. The brand company keeps a piece of the action, and the savings don’t reach their full potential.

The RAND Corporation found this pattern across dozens of drugs. The result? Billions in lost savings for insurers, Medicare, and patients over time.

Who benefits-and who loses?

Brand-name companies benefit the most. They keep control over pricing, maintain market share, and avoid the full price collapse that comes with true generic competition. They also get to collect revenue from both the brand and the generic version-sometimes even before the first generic even starts selling.

First generic manufacturers lose. They spent years and millions of dollars challenging patents, only to see their reward diluted. Many mid-sized generic firms now say the profitable window for a first generic has shrunk to just 45-60 days in many drug categories. Some have stopped filing patent challenges altogether.

Patients and payers are caught in the middle. Yes, prices drop. But not as much as they should. And because authorized generics aren’t counted as true competitors in Medicare price negotiations (thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022), the system doesn’t even recognize the full impact of this maneuver.

Why do authorized generics exist at all?

Some argue they’re a good thing. The Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM) says authorized generics increase competition and get cheaper drugs to patients faster. They point to drugs like Lipitor (atorvastatin) and Prilosec (omeprazole), where authorized generics helped drive down prices quickly.

That’s true-but only in isolation. The bigger picture shows a pattern: authorized generics are used as weapons, not gifts. They’re timed to sabotage the incentive system designed by Congress in 1984’s Hatch-Waxman Act. That law was meant to reward the first challenger, not let the brand company undercut them before they even got started.

It’s like giving a head start to the runner who’s supposed to win the race-then letting the favorite sprint in right behind them and steal the prize.

What’s changing in the regulatory landscape?

The FDA approved 80 first generics in 2017, a record at the time. But the approval process is still slow. Under GDUFA, the average review takes 10 months-but backlogs can stretch it to three years. Meanwhile, authorized generics can launch in days.

The FTC has taken action against some “pay-for-delay” deals where brand companies pay generics to delay entry. But authorized generics? They’re legal. And they’re growing. Evaluate Pharma predicts they’ll make up 25-30% of all generic prescriptions by 2027, up from 18% in 2022.

Drug categories most affected? Cardiovascular drugs (32%), central nervous system drugs (24%), and metabolic disorders like diabetes (18%). Right now, drugs like Eliquis and Jardiance are the next battlegrounds.

What does this mean for the future?

First generic companies are adapting. Some are building faster launch pipelines. Others are diversifying their portfolios so they don’t rely on one blockbuster generic. A few are even partnering with brand companies to get authorized generic rights themselves-turning the tables.

But the system is still tilted. The 180-day exclusivity rule was meant to break monopolies. Instead, it’s become a target for more sophisticated monopolistic behavior.

Until regulators redefine what counts as real competition, patients will keep paying more than they should. And the companies that fight to bring generics to market will keep getting outmaneuvered by the very brands they’re trying to replace.

12 Comments

Dave Old-Wolf

January 8 2026So the brand just puts out a fake generic to steal the first mover’s reward? That’s not competition, that’s theft with a label.

Why does the FDA let this happen? It’s like letting the referee join the game after the whistle.

Patients pay more, and the system calls it ‘fair’.

Prakash Sharma

January 10 2026USA thinks it’s smart but this is just corporate greed dressed up as innovation. In India, we see generics as lifelines-not tools for monopoly games. This whole system is broken and it’s the poor who bleed.

When will the world wake up?

Kristina Felixita

January 11 2026okay so like… the brand company just… copies itself?? and calls it a generic??

that’s wild. i mean, if i made a knockoff of my own sandwich and sold it as ‘budget club’… would that be legal??

also why is no one screaming about this??

my uncle takes Lyrica and he’s still paying 50 bucks a month… this is insane.

someone please fix this before my grandma can’t afford her meds anymore

Evan Smith

January 11 2026So the Hatch-Waxman Act was basically a ‘you go first, we’ll let you win’ deal… until the brand said ‘lol nope’ and walked in with a copy.

Brilliant. Just brilliant.

It’s like giving someone a head start in a race… then having the favorite sprint in wearing the same jersey.

Who’s the genius who thought this was a good loophole? Someone in pharma PR with a law degree and zero morals.

And we wonder why people hate Big Pharma.

Lois Li

January 12 2026I’ve been working in pharmacy for 18 years and this is the most frustrating part of the job. We see patients who get their meds cheaper-but not cheap enough. We know the real savings aren’t happening. And we’re stuck explaining why a ‘generic’ still costs $40 when it should be $5.

It’s not the pharmacists’ fault. It’s the system.

And honestly? We’re tired of being the ones who have to break the bad news.

christy lianto

January 13 2026They didn’t just break the system-they rebuilt it to serve themselves.

First generic companies risked everything. They sued. They spent millions. They waited years.

And then the brand just… walked in with a disguise and split the pie.

It’s not just unfair. It’s cruel.

And now people wonder why no one wants to be the first to challenge a patent anymore.

Because why fight if you’re just gonna get stabbed in the back?

swati Thounaojam

January 14 2026so authorized generic = brand in disguise? yeah that makes sense. sad but true. no wonder prices dont drop enough. its not really competition.

Annette Robinson

January 14 2026It’s important to recognize that while authorized generics may appear to increase access, they fundamentally undermine the incentive structure designed to encourage generic innovation. The result is a market distortion that prioritizes corporate profit over public health. Regulatory reform is not optional-it’s imperative.

Luke Crump

January 15 2026What if… the whole idea of ‘generic’ is a lie?

What if ‘brand’ and ‘generic’ are just two faces of the same monster?

Maybe the real drug isn’t the pill-it’s the system that makes us believe we’re getting a deal.

We’re not consumers. We’re lab rats in a pricing experiment.

And the scientists? They’re wearing suits and calling themselves ‘innovators.’

What’s next? A ‘generic’ version of oxygen?

Someone’s gonna patent air soon. I just know it.

Aubrey Mallory

January 15 2026I’ve talked to small generic manufacturers who say they’re walking away from first-filer applications. Why? Because the reward’s been gutted.

It’s not just about money-it’s about trust. If you’re going to risk everything, you need to believe the rules are fair.

They’re not.

And until Congress fixes this, we’re just playing pretend competition.

Molly Silvernale

January 15 2026Imagine if the Mona Lisa was painted by da Vinci… then da Vinci’s cousin made a copy, slapped on a ‘generic’ sticker, and sold it for half the price-right next to the original. People would call it art. But if you asked who really owns the legacy? The cousin gets the cash. The artist gets the silence.

That’s what’s happening here.

And we’re the ones who paid for the brushstrokes.

But nobody’s holding the brush anymore.

Just the marketing team.

Joanna Brancewicz

January 16 2026Authorized generics create a regulatory externality: they suppress price elasticity during the 180-day exclusivity window, reducing the expected consumer surplus by 30-40% compared to true multi-generic entry. This is well-documented in the RAND study and contradicts the foundational premise of the Hatch-Waxman Act’s incentive structure.