On-Target vs Off-Target Drug Effects: How Side Effects Really Happen

Side Effect Analyzer

When you take a pill for high blood pressure, diabetes, or cancer, you expect it to help. But sometimes, it causes nausea, rashes, or weird fatigue you didn’t sign up for. Why? It’s not random. Side effects aren’t accidents-they’re predictable outcomes of how drugs interact with your body. And the key to understanding them lies in two simple but powerful ideas: on-target and off-target effects.

What Are On-Target Effects?

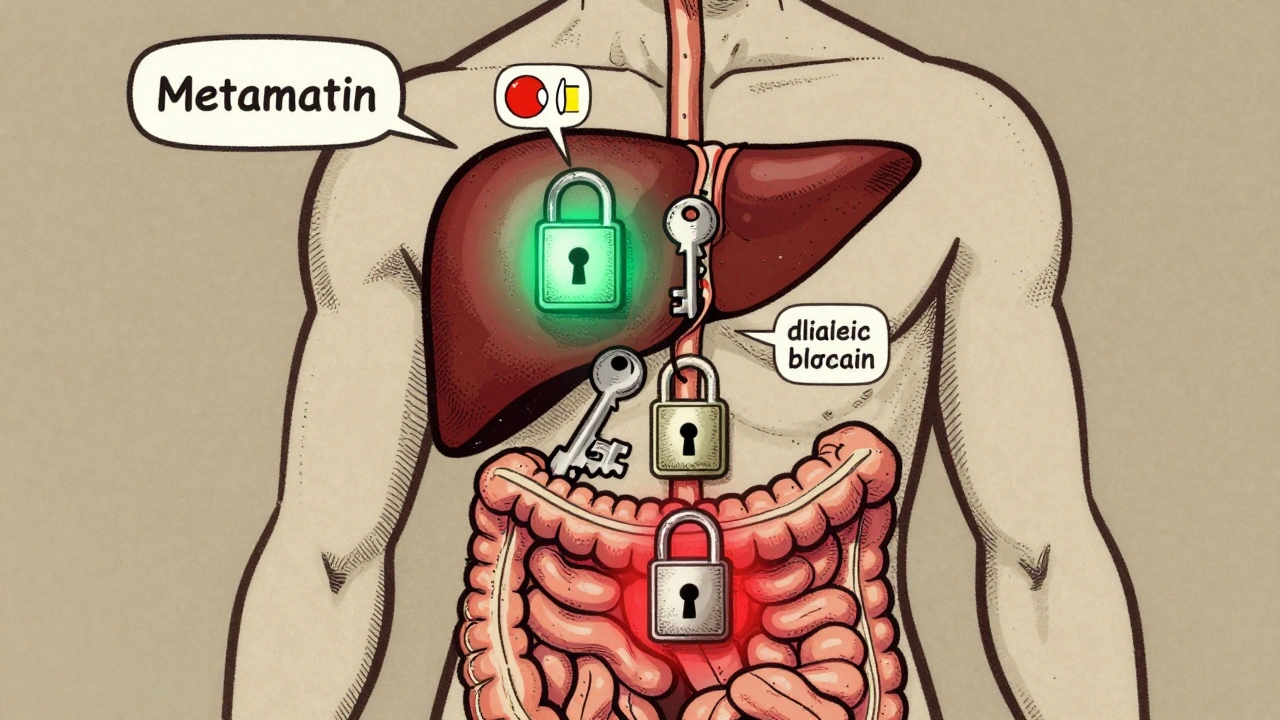

On-target effects happen when a drug does exactly what it’s supposed to do-but in the wrong place. Think of it like a key that fits the right lock, but turns it in a room you didn’t mean to enter. Take metformin, a common diabetes drug. It works by reducing glucose production in the liver. That’s the goal. But it also slows down digestion in the gut. Result? Diarrhea, bloating, stomach cramps. That’s not a flaw-it’s the same mechanism working too hard in a different tissue. This is why 68% of patients on EGFR inhibitors for cancer get bad skin rashes. The drug blocks a protein that helps skin cells grow, just like it blocks the cancer version. The side effect isn’t a mistake. It’s the target being hit where it shouldn’t be. Statins, used to lower cholesterol, are another classic example. They block HMG-CoA reductase, an enzyme in the liver. That’s on-target. But that same enzyme is also active in muscle cells. So when statins reduce cholesterol, they can accidentally weaken muscle tissue. That’s why some people get muscle pain or even dangerous rhabdomyolysis. It’s not random. It’s biology. On-target side effects are common in drugs that hit targets found in multiple tissues. Cancer drugs, heart meds, and hormone therapies are full of them. About 38% of all on-target toxicity reports in the last decade came from cardiovascular drugs. And here’s the thing: doctors expect them. A 2021 survey of over 1,200 physicians found that 82% saw on-target side effects as “expected and manageable.” You don’t stop the drug-you manage the symptom.What Are Off-Target Effects?

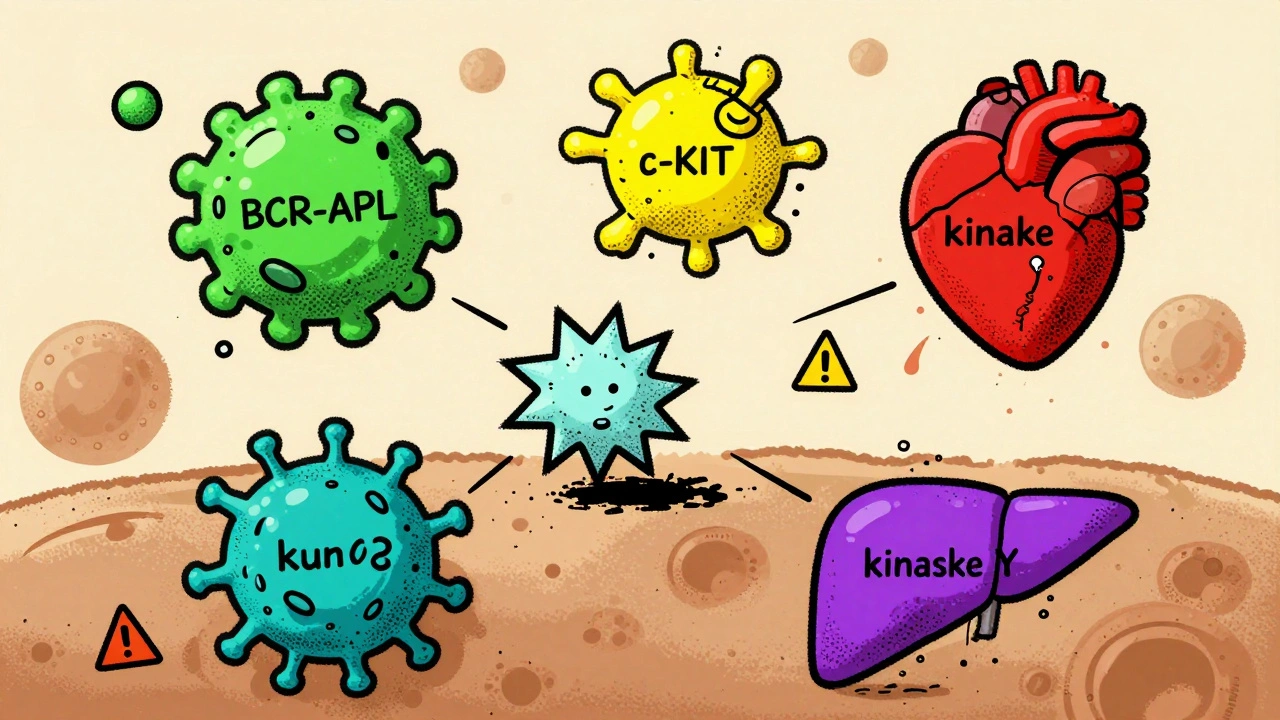

Off-target effects are the sneaky ones. They happen when a drug accidentally binds to something it wasn’t designed to hit. It’s like using a screwdriver to open a can of paint. It might work-but you’ll make a mess. Most small-molecule drugs aren’t perfectly selective. Studies show they interact with an average of 6.3 unintended targets at therapeutic doses. Kinase inhibitors-used in cancer-are especially messy. One drug might bind to 25-30 different kinases. That’s why drugs like imatinib (Gleevec) can treat leukemia (by blocking BCR-ABL) but also cause swelling or fluid retention (by hitting c-KIT, a different kinase involved in fluid balance). Off-target effects are why some drugs get pulled from the market. Chloroquine, once used for malaria, was later tried for COVID-19. But its real action wasn’t on the virus-it was on lysosomes and endosomes, disrupting cell chemistry in ways that could cause heart rhythm problems. That’s off-target. And it’s unpredictable. You can’t always see it in lab tests. That’s why about 65% of Phase II drug failures are due to off-target toxicity, according to FDA data. Even drugs that seem clean can surprise you. A 2019 study showed that four different statins triggered wildly different gene responses in three types of human cells. Only one pathway-HMG-CoA reductase-was consistently affected. Everything else? Random noise. That’s off-target activity in action.Why Do Some Drugs Have More Off-Target Effects Than Others?

It comes down to chemistry and design. Small molecule drugs-pills you swallow-are usually simpler and smaller. That makes them more likely to slip into the wrong protein pockets. Biologics, like antibody drugs (Herceptin, Keytruda), are bigger, more complex, and stickier. They’re designed to lock onto one specific target. As a result, they average only 1.2 off-target interactions, compared to 6.3 for small molecules. But even biologics aren’t perfect. Trastuzumab targets HER2, a protein overexpressed in some breast cancers. That’s clean. But because HER2 is also present in small amounts in heart tissue, long-term use can lead to heart weakness. That’s still on-target-but in a sensitive organ. So the line isn’t always clear. Kinase inhibitors are the worst offenders. They account for 42% of all off-target toxicity reports in the FDA’s database from 2015-2020. Why? Because kinases are structurally similar. If a drug fits one, it often fits others. That’s why companies like Genentech and Novartis spend millions on tools like KinomeScan-to map every possible interaction before a drug even reaches humans.

Can Off-Target Effects Be Good?

Absolutely. Some of the most successful drugs started as mistakes. Sildenafil (Viagra) was developed for angina. It worked by relaxing blood vessels via phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition. But in trials, patients reported something else: stronger erections. Turns out, that enzyme is also in penile tissue. The “side effect” became the main use. Thalidomide was pulled in the 1960s after causing severe birth defects. Later, scientists found it suppressed inflammation and boosted immune activity-useful for multiple myeloma. Today, it’s a lifesaver for cancer patients, used under strict controls. Even statins, known for muscle pain, may have off-target benefits. Some studies suggest they reduce inflammation in arteries beyond just lowering cholesterol. That’s why they’re now used for heart disease prevention even in people with normal cholesterol. The lesson? Not all off-target effects are bad. Some are hidden opportunities. The trick is knowing which ones are dangerous and which ones are useful.How Do Scientists Spot These Effects Before Patients Take the Drug?

Drug companies don’t wait for people to get sick to find out what a drug does. They use advanced tools to predict problems early. One method is chemical proteomics-flooding cell extracts with a drug and seeing what proteins stick to it. Another is transcriptomics: measuring changes in gene activity after drug exposure. A 2019 study used Cap Analysis of Gene Expression (CAGE) to compare how statins affected gene expression. They found that while gene-level changes were messy, pathway-level changes (like immune activation or cholesterol metabolism) were consistent. That’s how they separated on-target from off-target signals. Machine learning now helps too. The Open Targets Platform, used by 87% of top pharma companies, combines genetic, chemical, and clinical data to predict which targets might cause side effects. In January 2023, they upgraded it with AI that predicts off-target effects with 87% accuracy based on a drug’s chemical shape. Regulators are catching up. The FDA and EMA now require at least two independent methods to test for off-target effects before approving new drugs. For gene therapies, that’s mandatory. That’s a big shift from 2015, when only 35% of companies did full off-target screening. Now, it’s 78%.

14 Comments

Jack Arscott

December 2 2025This is why I always ask my doc if it's on-target or off-target now 😅 I used to think my stomach issues from metformin meant I was allergic. Turns out I just have a very enthusiastic liver. 🤓

Matt Dean

December 2 2025Of course the pharma bros are gonna call it 'predictable biology' when their $2M pill gives you diarrhea. Meanwhile, I'm the one paying for it. #CorporateMedicine

Walker Alvey

December 3 2025So drugs are just clumsy teenagers with keys to your body and no sense of boundaries? Cool. So why are we surprised when they break stuff?

Shannon Gabrielle

December 4 2025USA spends billions on this shit while people can't afford insulin. Meanwhile your statin gives you muscle pain but your CEO gets a yacht. This isn't science. It's capitalism with a lab coat.

ANN JACOBS

December 6 2025It is truly remarkable how the human body functions as an intricate, interconnected system wherein even the most precisely engineered pharmaceutical agents inevitably engage with non-targeted biological pathways. The implications for personalized medicine are profound, and I believe we are on the cusp of a paradigm shift in therapeutic safety.

Nnaemeka Kingsley

December 6 2025So metformin give you diarea? I thought it was just my food. Lol. My cousin in Nigeria say same thing. So its not just me? Good to know.

Kshitij Shah

December 7 2025Back home in Mumbai, we used to say 'medicine is just poison with a prescription'. Now I get it. That statin? It's not helping your heart. It's just making your legs weak. But hey, at least your cholesterol is low, right?

Souvik Datta

December 8 2025There's a beautiful paradox here: the very mechanisms that heal us also harm us. Life doesn't come with clean switches. It's all gradients. Maybe the real cure isn't a better drug-but a better understanding of ourselves.

James Steele

December 8 2025The kinetic selectivity profiles of small-molecule kinase inhibitors are fundamentally constrained by the conserved ATP-binding clefts across the kinome. Consequently, polypharmacological off-target engagement is not merely probabilistic-it is deterministic. Hence, the clinical toxicity burden is an emergent property of structural homology, not pharmacological negligence.

soorya Raju

December 10 2025They say 'on-target' but what if the target is a lie? What if the whole 'cholesterol causes heart disease' thing is a scam? What if statins are just making us weak so we buy more meds? #DeepStatePharma

Dennis Jesuyon Balogun

December 11 2025This is why we need community-based pharmacovigilance. In my village, elders know which herbs counteract side effects. We don’t wait for FDA reports. We talk. We share. We heal together. This isn't just science-it's survival.

Grant Hurley

December 11 2025I got the skin rash from that cancer drug and thought I was dying. Turns out it's just my skin being extra loyal to the same protein the drug is killing in the tumor. Kinda sweet? Like a weird biological hug? 🤷♂️

Lucinda Bresnehan

December 12 2025I work in a clinic and I see this every day. One patient thought her fatigue from thyroid med was 'just stress'. Turned out it was the drug hitting her adrenal receptors. Always check the mechanism. Always.

Sean McCarthy

December 12 2025I'm a doctor. I've seen this. On-target side effects are predictable. Off-target are dangerous. But most patients don't know the difference. And that's why they stop taking their meds. And then they die. So stop being cute. Just tell them: 'This is normal. This is not.'