The Difference Between Medication Side Effects and Adverse Drug Reactions Explained

Medication Reaction Assessment Tool

Symptom Assessment

Reaction Analysis

Unknown Reaction Type

Side Effect Indicator: Common reaction seen in clinical trials at normal doses.

Adverse Reaction Indicator: Predictable reaction (Type A) or immune-mediated reaction (Type B).

Adverse Event Indicator: Unlikely related to medication - likely coincidence or other cause.

Key Assessment Points

Recommended Actions

Important: This assessment is for educational purposes only. Consult your healthcare provider for medical advice.

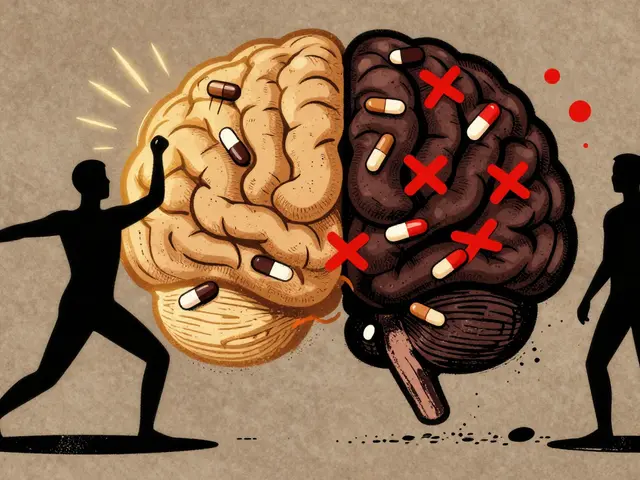

When you start a new medication, your doctor might tell you it could cause side effects. But what does that really mean? And what’s the difference between a side effect and an adverse drug reaction? These terms are often used interchangeably - even by some healthcare providers - but they’re not the same. Getting this right matters. Misunderstanding these terms can lead to unnecessary fear, stopping life-saving drugs, or missing real dangers.

What Is a Side Effect?

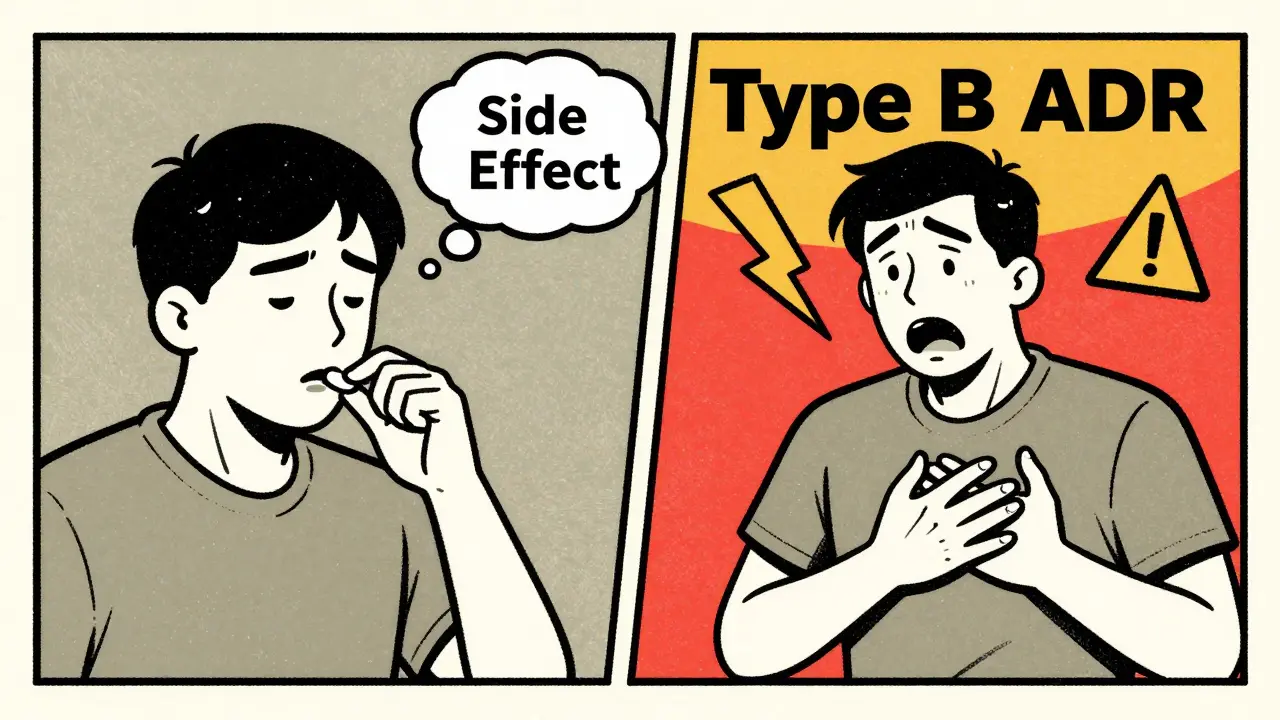

A side effect is a known, predictable reaction to a medication that happens because of how the drug works in your body. It’s not a mistake. It’s not an accident. It’s built into the drug’s design. For example, if you take an antihistamine for allergies and feel drowsy, that’s a side effect. The drug blocks histamine to reduce sneezing - but histamine also helps keep you awake. So drowsiness is a direct, expected result. Side effects are identified during clinical trials. Researchers compare people taking the drug with those taking a placebo. If nausea happens in 30% of the drug group but only 5% in the placebo group, that’s a confirmed side effect. It’s not random. It’s linked to the drug. Common side effects include dry mouth from antidepressants, constipation from painkillers, or increased urination from diuretics. These are usually mild and often fade over time as your body adjusts. The FDA lists these in drug labels because they’re well-documented and happen at normal doses.What Is an Adverse Drug Reaction?

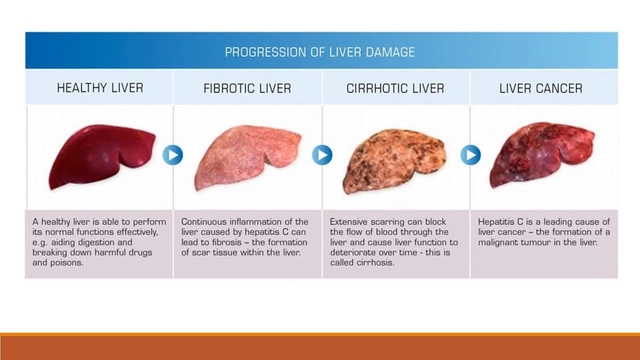

An adverse drug reaction (ADR) is a broader term. It includes side effects - but also other harmful responses that aren’t always predictable. The World Health Organization defines it as a response to a drug that’s noxious and unintended, occurring at normal doses. There are two main types of ADRs:- Type A (Augmented): These are predictable, dose-related, and make up 80-85% of all reactions. They’re often the same as side effects. Think liver damage from too much acetaminophen, or stomach bleeding from long-term NSAID use. They happen because the drug’s chemistry interacts with your body in a known way.

- Type B (Bizarre): These are unpredictable. They’re not tied to the drug’s main action. For example, a rash or anaphylaxis after taking penicillin. These aren’t dose-dependent. You could take one pill and have a life-threatening reaction, even if you’ve taken it safely before. This is an immune response - not a side effect.

What’s an Adverse Event?

An adverse event is anything bad that happens after you take a drug - whether it’s caused by the drug or not. It’s the starting point, not the conclusion. Imagine you’re on blood pressure medication and you fall and break your hip two weeks later. That’s an adverse event. But is it caused by the drug? Maybe. Maybe not. Maybe you were dizzy from low blood pressure. Maybe you tripped on a rug. Maybe you had a stroke. Until you prove the drug caused it, it’s just an event. Adverse events are reported all the time. The FDA gets over a million every year. But only about 32% of them turn out to be true adverse drug reactions after investigation. The rest? Coincidence, underlying illness, or errors like taking the wrong dose.

Why the Confusion Matters

A 2021 survey by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices found that 68% of healthcare workers mix up these terms in patient records. That’s dangerous. If a patient says, “I had a headache after taking the pill,” and the doctor writes “side effect,” it sounds like it’s normal and expected. But if the headache was actually a sign of high blood pressure caused by the drug - a Type A reaction - it needs monitoring. Calling it a “side effect” might make someone think it’s harmless. Worse, patients often stop taking medications because they think every bad feeling is a side effect. A 2021 study showed 43% of people quit life-saving drugs like statins or blood thinners after misinterpreting common symptoms like fatigue or muscle pain as side effects. In reality, those symptoms were unrelated - maybe from stress, lack of sleep, or aging. The American Medical Association now requires doctors to use “adverse reaction” only when causality is confirmed. Otherwise, it’s an “adverse event.” This isn’t just semantics. It affects insurance claims, safety reporting, and patient trust.Real-World Example: Apixaban and Headaches

A 2020 JAMA study looked at apixaban, a blood thinner. Researchers tracked headaches in patients taking the drug versus those on a placebo. Both groups had headaches at nearly the same rate: 12.3% vs. 11.8%. That means headaches weren’t a side effect of apixaban. They were just common in the general population. But major bleeding? That happened in 2.1% of the apixaban group and only 0.5% in the placebo group. That’s a confirmed side effect - and a serious one. The drug causes it. It’s not random. It’s predictable. And it’s documented. If someone on apixaban gets a headache, telling them it’s a side effect is misleading. It’s an adverse event - possibly unrelated. But if they start bleeding internally, that’s a side effect. And it needs immediate action.How Doctors Tell the Difference

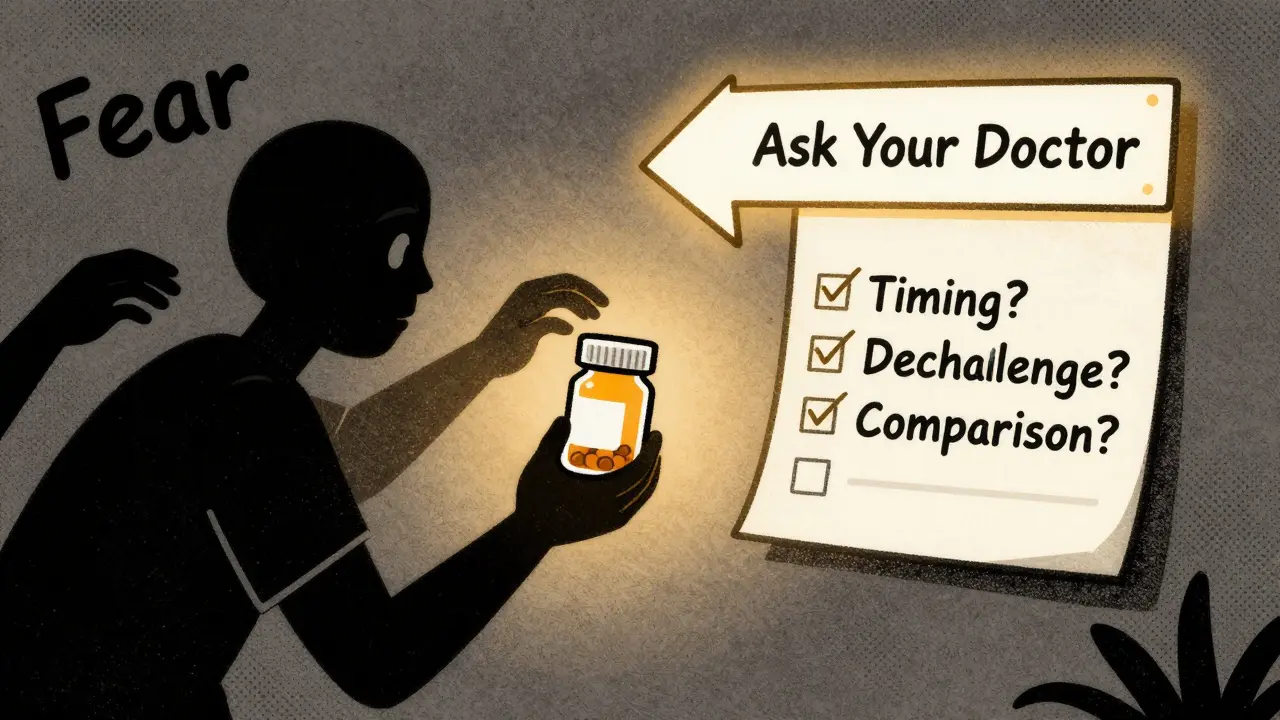

There’s a process. It’s not guesswork. At top hospitals like UCSF, staff use a 3-step check:- Timing: Did the symptom start after taking the drug? How long after?

- Dechallenge/Rechallenge: If the drug is stopped and the symptom goes away, then restarted and it comes back - that’s strong evidence of a link.

- Comparison: Does this reaction match known patterns in databases like Micromedex or the WHO Drug Dictionary?

What This Means for You

You don’t need to be a doctor to understand this. When you’re told a drug has side effects, ask: “Is this something that happens to most people on this drug? Is it expected?” If yes, it’s likely a side effect. If it’s rare, sudden, or doesn’t match what’s listed, it might be something else. If you feel something new after starting a medication:- Don’t panic. Not every odd feeling is caused by the drug.

- Don’t stop the medication without talking to your doctor.

- Write down when it started, how bad it is, and if anything made it better or worse.

- Ask: “Is this a known side effect? Or could it be something else?”

13 Comments

Solomon Ahonsi

February 2 2026This whole post is just a fancy way of saying doctors don't know what they're talking about and you should just Google everything. I took lisinopril and got a cough. They called it a side effect. Turns out it was the damn drug. No magic 3-step checklist needed. Just stop taking it and see if you stop hacking.

George Firican

February 4 2026There's a deeper philosophical layer here that most people miss. The language we use to describe bodily experiences is inherently flawed-we assign causality where there may only be correlation, and we mistake familiarity for understanding. When we label a headache as a 'side effect,' we're not just describing physiology-we're constructing a narrative of control, of medical authority over the chaotic reality of the human body. The real danger isn't misclassification-it's the illusion that medicine can neatly categorize suffering. Maybe the headache isn't caused by the drug. Maybe it's caused by the fear that it might be. And isn't that the most dangerous reaction of all?

Matt W

February 6 2026I’ve been on antidepressants for 5 years and I still get anxious when I read stuff like this. But honestly? This cleared up so much. I used to think every weird feeling was the meds. Turns out, a lot of it was just stress or lack of sleep. Thanks for breaking it down without jargon. I’ll actually ask my doctor next time instead of just quitting cold turkey like I did last year. 😅

Anthony Massirman

February 7 2026Side effect = expected. ADR = scary. AE = probably nothing. Done.

Eli Kiseop

February 9 2026so if i get dizzy after taking blood pressure med is that side effect or adre or just event and why does it matter if im still dizzy

Ellie Norris

February 11 2026Love this post! Just wanted to add-my mum had a Type B reaction to amoxicillin at 72, never had an issue before. Rash, swelling, almost went to ER. Docs called it 'allergy' but it's actually an ADR. Important to note these can pop up anytime, even after years of safe use. Always report weird stuff, even if it seems small. 🙏

Marc Durocher

February 12 2026So let me get this straight-doctors are too lazy to use the right terms, patients panic over headaches, and we’re all just one bad Google search away from quitting warfarin? Brilliant. The system is designed to confuse us so we don’t question why we’re on 17 pills at 65. But hey, at least the AI is here to save us. Next up: ChatGPT prescribing your statins.

larry keenan

February 12 2026The operational distinction between adverse events and adverse drug reactions is critical for pharmacovigilance data integrity. Failure to adhere to WHO and FDA definitional frameworks introduces significant noise into signal detection algorithms, thereby compromising the validity of post-marketing surveillance outcomes. This is not merely semantic-it is a foundational pillar of clinical safety infrastructure.

Nick Flake

February 13 2026THIS. 🙌 This is the kind of post that makes me want to hug a pharmacist. I used to think every little twinge was the drug trying to kill me. Now I know: if it’s not on the list, it’s probably just life being life. And if it’s bleeding? Yeah, that’s not ‘just a side effect.’ That’s your body screaming. Don’t ignore it. Don’t overreact. Just… call your doctor. 🌈

Akhona Myeki

February 15 2026In South Africa, we don't have the luxury of debating semantics. We have patients who die because they stop their ARVs because they got a rash. This post is American privilege wrapped in medical jargon. In our clinics, we say: if it's bad, stop it. If it's not listed, report it. No philosophy. No 'adverse events.' Just survival. You think your headache matters? We fight for pills every month.

Chinmoy Kumar

February 16 2026Really helpful post! I work in a pharmacy in India and we see so many people stop meds because they think every stomach ache is a side effect. We try to explain but it's hard when people only read the warning label. This breakdown is gold. I'll share it with my team. One typo: 'adverse event' not 'adverse even' 😅

Brett MacDonald

February 18 2026so like… if i get tired on statins is it a side effect or just my age or did i eat too much pizza last night or is it the universe telling me to slow down idk man

Sandeep Kumar

February 19 2026Pathetic. In India we don't need your Western overthinking. If the drug makes you feel bad you stop it. Period. Your fancy WHO classifications mean nothing when your child needs insulin and you're choosing between medicine and rice. This is not a philosophy seminar. It's survival. Stop pretending complexity makes you smarter.